Congress may have narrowly avoided yet another shutdown of the United States government last week — but only by punting questions about the country’s solvency down the road, with the Treasury warning of a potential “catastrophic” default on debts.

With just hours to spare, the House and Senate passed a bill late Thursday to temporarily fund the government through Dec. 3, with legislation signed by President Joseph R. Biden Jr. It extends federal agencies’ current spending rates and provides $28.6 billion to address natural disasters like Hurricane Ida, $6.3 billion for resettlement assistance for Afghan refugees and $2.5 billion for the care and shelter of unaccompanied migrant children who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border.

But the resolution did not include any language to raise or suspend the debt limit, keeping the United States on the brink of defaulting on its loans for the first time.

The White House and Congress now have a few more weeks to negotiate deals on 12 appropriations bills for fiscal year 2022 — nine of which the House has passed.

“There’s so much more to do,” Biden said. “But the passage of this bill reminds us that bipartisan work is possible, and it gives us time to pass longer-term funding to keep our government running and delivering for the American people.”

The bill’s success followed a failed attempt earlier in the week to pass similar legislation, which contained a provision to suspend the debt limit. Republicans in the Senate blocked it, saying they would only support a short-term funding bill. After its passage, the Senate agreed to a motion to bring the House-passed debt ceiling measure — which would lift the borrowing limit until December 2022 — to the floor via a party-line, 50-43 vote with seven Republicans missing.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) said he would ask his chamber to consider the legislation next week, but it is expected to fail amid a GOP filibuster.

The standoff over the debt ceiling comes just days after Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned that the department could run out of money as soon as Oct. 18, putting the U.S. in danger of a “catastrophic” sovereign debt default.

“If to finance those spending and tax decisions, it’s necessary to issue additional debt, I believe it’s very disruptive to put the president and myself, the Treasury secretary, in a situation where we might be unable to pay the bills that result from those past decisions,” Yellen said in a House committee hearing Thursday.

“I think it would be catastrophic for the economy and for individual families.”

Congress last agreed to suspend the debt limit in 2019 until July 31 of this year. The Treasury has since been using emergency measures to pay America’s bills. Increases to the debt limit have historically been through bipartisan votes, with Democrats and Republicans increasing the limit three times under President Donald J. Trump.

However, this time around, Republicans have opposed lifting the debt ceiling, pointing to a $3.5-trillion spending bill that Democrats are trying to pass through the budget-reconciliation process with no GOP votes. Republicans argue the Democrats should try to raise the limit through the same process, without GOP support.

“The conclusion to draw from this week is very clear — clumsy efforts at partisan jams do not work,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said on the floor on Thursday. “We’re able to fund the government today because the majority accepted reality. The same thing will need to happen on the debt limit next week.”

However, it’s not clear the Democrats would be able to push such a bill through the Senate, with two of its own senators opposing the $3.5-trillion price tag.

Democrats have countered that the GOP should shoulder the political responsibility for a debt-limit suspension, and have accused their counterparts of letting partisan fighting jeopardize the U.S. economy. They say the reconciliation process would be too time-consuming and complex to address the $28.8-trillion national debt.

“Republicans need to get out of the way, so Senate Democrats can address the issue quickly and without needlessly endangering the stability of our economy,” Schumer said.

Some, though, remain hopeful, since the parties “agree that we should not default.”

“Republicans certainly haven’t said that they support defaulting on our debt. In fact, they’ve come out and said quite the opposite,” Rachel Snyderman, associate director for economic policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center, told Zenger. “Right now, it’s not that Republicans … have been against raising the debt limit. … It’s that both parties want to discuss different policy options when it comes to addressing the debt limit.”

“The issue, of course, is the reconciliation bill that Democrats have on the table, and that’s why Republicans don’t want to support raising the debt limit,” she said.

“But it’s important to look at the debt limit as a way to finance our past obligations — all the bills that have come due and the accumulation of tax and spending priorities through all past administrations, Republican and Democrat alike.”

As the Thursday votes and negotiations carried late into the night, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) said she would also delay her chamber’s scheduled vote on the $1.2-trillion Senate-passed infrastructure bill amid a rebellion within her party.

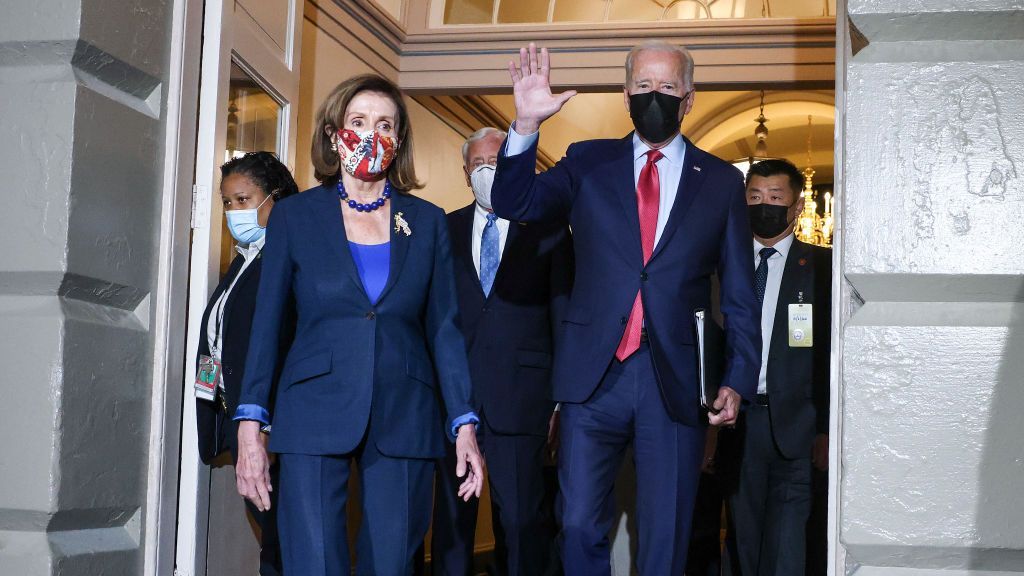

House members returned on Friday to continue pursuing a deal on the measure — and Biden also made a visit to the Capitol, as Democrats remained divided on the separate-but-linked $3.5-trillion spending bill, which funds what the Biden administration has deemed “human infrastructure.”

Some progressive members have vowed to vote against the $1.2-trillion infrastructure legislation unless a broader agreement on the $3.5-trillion spending bill is made with party moderates, some of whom want to lower its price tag.

“We’re on a path,” Pelosi said, promising the Democrat-controlled House would vote on the infrastructure bill by Oct. 31, giving lawmakers more time to reach a deal.

Thanks to slim majorities in the House and Senate, Democrats must remain virtually united to pass both the infrastructure and spending legislation. Some, like Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.), have proposed a spending bill price tag of $1.5 trillion — even as progressives have mostly refused to budge on the $3.5 trillion proposal.

Still, some progressives have indicated they may be willing to compromise.

“I accept that there’s going to have to be give and take,” said Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.).

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) similarly noted there is room for negotiation.

“I’m a realist too,” he said. “Concessions will be made. And we’re certain of that.”

Edited by Alex Willemyns and Matthew B. Hall

The post All Eyes Turn To Debt Ceiling After Congress Narrowly Avoids Government Shutdown appeared first on Zenger News.