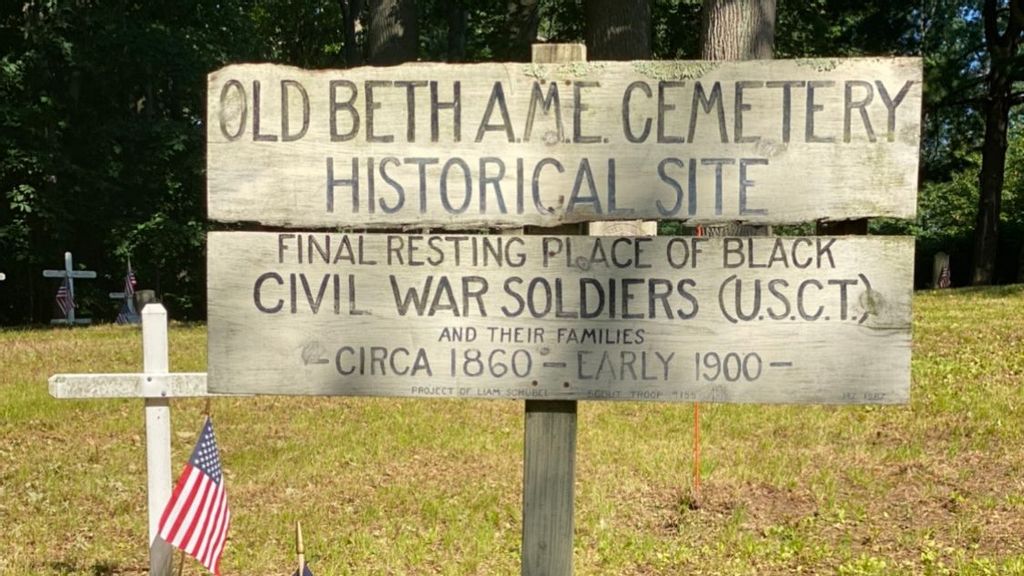

FREEHOLD, N.J. — Volunteers gathered here on June 26 to clean a rundown burial ground for black Civil War veterans — the first step in a local community campaign to turn the site into a historical landmark and help restore the legacy of soldiers who fought to end slavery in America.

More than 50 participants, including the young, old, and people from different races, spent their Saturday clearing away overgrown weeds, fallen trees and debris from the Squirrel Town Historical Cemetery, where an estimated 35 black Civil War veterans lay in rest.

Led by the Bethel AME Church, which owns the property, the massive clean-up became a community event to honor the heroes who helped secure the Union victory in May 1865.

“It’s history for not only the church, but also for the town, for people of color, and the United States,” said Rev. Ronald Sparks, the pastor at Bethel AME Church, about a mile from the cemetery. “It’s important for the descendants that their families be recognized, and that’s what we want to do,” he said. “It’s time to tell our story and get that story out there.”

The cemetery rests on a hill where the unpaved Illene Way and Old Monmouth Road meet, just off Route 522 on the west side of Freehold, N.J., in Monmouth County. The area known as Squirrel Town was once the home of segregated blacks who worked on farms in the area.

While it’s designated a historical site, it does not register on a GPS and is not visible from any main road. The church had lacked the funds and workforce to properly maintain the cemetery, Rev. Sparks told Zenger, but the church’s trustees decided to launch a social media campaign to fix that, soliciting support and setting a date to clean up the 2-acre property.

After the campaign was featured on a local news station, volunteers and neighbors of all ages and colors showed up, some bringing landscaping equipment to clear away the brush.

“It was time to take care of it because honored veterans shouldn’t be laid to rest in such a place,” said Robert “Babe” Warrington, one of the church’s trustees.

“We used to solicit help from the Boy Scouts, and even some inmates from jail have cleaned things up in the past. But it’s in a remote spot, and it’s hard to get equipment up there. It got to the point where we needed to do something. The response was tremendous.”

After President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, approximately 190,000 black men served as soldiers for the Union Army, while 19,000 joined the Navy. All were part of the United States Colored Troops, which grew to 175 regiments within the U.S. Army. For many alive today, the USCT validated abolitionist Fredrick Douglass’s proclamation “he who would be free must himself strike the blow.”

According to William Gladstone’s book “United States Colored Troops, 1863-1867,” an estimated 1,185 members of USCT came from New Jersey.

Historical records show the USCT regiments displayed courage and won victories on the battlefield. About 40,000 black soldiers died from either battle or disease before the Civil War ended in 1865 — a death rate about 35 percent higher than white Union troops.

Yet knowledge of the sacrifice of the troops remains sparse, even among locals.

“It’s important to know that even though there were segregated troops, these black fallen soldiers paid the ultimate price for the freedom that we have now,” Warrington said. “Unfortunately, things like this don’t get taught in the school system.”

“I don’t think a lot of the school systems around here know about Squirrel Town or other black cemeteries that exist,” he added. “I grew up in Freehold and didn’t know anything about Squirrel Town until I joined the church in 1989, and I’m 68 years old.”

The Bethel AME Church is also working on an updated list of those buried in Squirrel Town.

Among the names is Corp. David Limehouse, Co. A, 22nd USCT. Limehouse suffered a gunshot wound to his left hand while seeing heavy action at the “Siege of Petersburg” in Petersburg, Virginia, where a nine-month battle ended with a victory. He died in 1896.

Lewis Conover, who fought in Company H, of the 127th USCT, is another who now lies in rest in Squirrel Town.

He served from August 1864 to September 1865, and saw action at the First Battle at Deep Bottom Virginia, also part of the Siege of Petersburg. Conover was discharged at Brazos, Texas, before moving to Freehold, where he died in 1910 at the age of 65.

But it’s not only Civil War veterans.

Also buried is Pvt. James William, who died while serving in World War I. U.S. forces were segregated until after World War II.

Town pioneers are buried, too — including Alex and Julia Hawkins, whose children served in World War II.

“A lot of our history is forgotten. It’s swept under the rug,” said Tracey Reason, the great-great-granddaughter of Alex and Julia Hawkins. “History likes not to give homage to black people. But these lives and legacies are too important to be forgotten.”

Kelly Guerra, who is Reason’s niece and also a member of the Bethel AME Church, said she is scouring the Internet and archives to gather names of others buried in the cemetery.

Guerra told Zenger she plans to send the list of names to the Veterans Administration, which provides free headstones in recognition of each veteran’s service. “I’m glad people are finding out about the history of Squirrel Town and about Bethel and their own people,” she said. “We’re also connecting family members with history they never knew.”

Capt. Robert C. Meyer of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, which helps clean up and restore grave markers across the Tri-State area, also attended the clean-up and put Grand Army of the Republic plaques alongside on broken or unreadable gravestones.

“Honoring any veteran by clearing an unmarked over-grown grave is very important,” Capt. Meyer said. “It adds to the community when you clean up these kinds of areas and bring them back to light. We still need to get some headstones out there, some new signage and other things that need to be addressed. The veterans buried there deserve that.”

About a half-acre of the property still needs clearing.

Long-term plans call for a fence, new signs, and crosses. A flag pole to make the cemetery easier to locate is also planned. Neighbors who border the property have lent their support.

“Since our clean-up, we’ve gotten a lot of calls and a lot of interest in the cemetery,” Rev. Sparks said. “It’s obviously important to people, especially when you’re talking about civil war soldiers and the history of families in this area. This is a predominantly white county. But people both black and white want to know the story.”

The church is targeting Veterans Day as the first official celebration of the restoration.

“We want to hold ceremonies there on Veterans Day, Memorial Day, and Juneteenth,” Rev. Sparks said. “These will be annual events that will help us tell the story so young people can understand the history they may or may not learn in school.”

“We want to be a historical site where when people visit Freehold, this is a stopping place as well as the original church. It’s not just our church history and New Jersey history; it’s U.S. history.”

(Edited by Alex Willemyns and Hugh Dougherty)

The post Black Civil War Veterans’ Burial Ground Is Restored By Church To Honor Their Legacy appeared first on Zenger News.